Join our team of surveyors, taking a close look at what is underfoot.

The January day dawns crisp and cold. I meet the rest of the team and we plan the day, inspecting the map to decide the area that each of us are going to cover. Over the next few weeks, we will walk almost every square metre of this moor, between us.

The January day dawns crisp and cold

The aim is to closely inspect the moor, looking for opportunities to make improvements to the condition of the blanket bog habitat. These interventions will slow water down to rewet the moor, and reduce the risk of flooding below. Rewetting the moor will enhance the boggy habitat, improving conditions for wet-loving bog species including sphagnum moss. In turn, these plants will help keep the peat where it is, eventually building new peat, helping reduce carbon emissions.

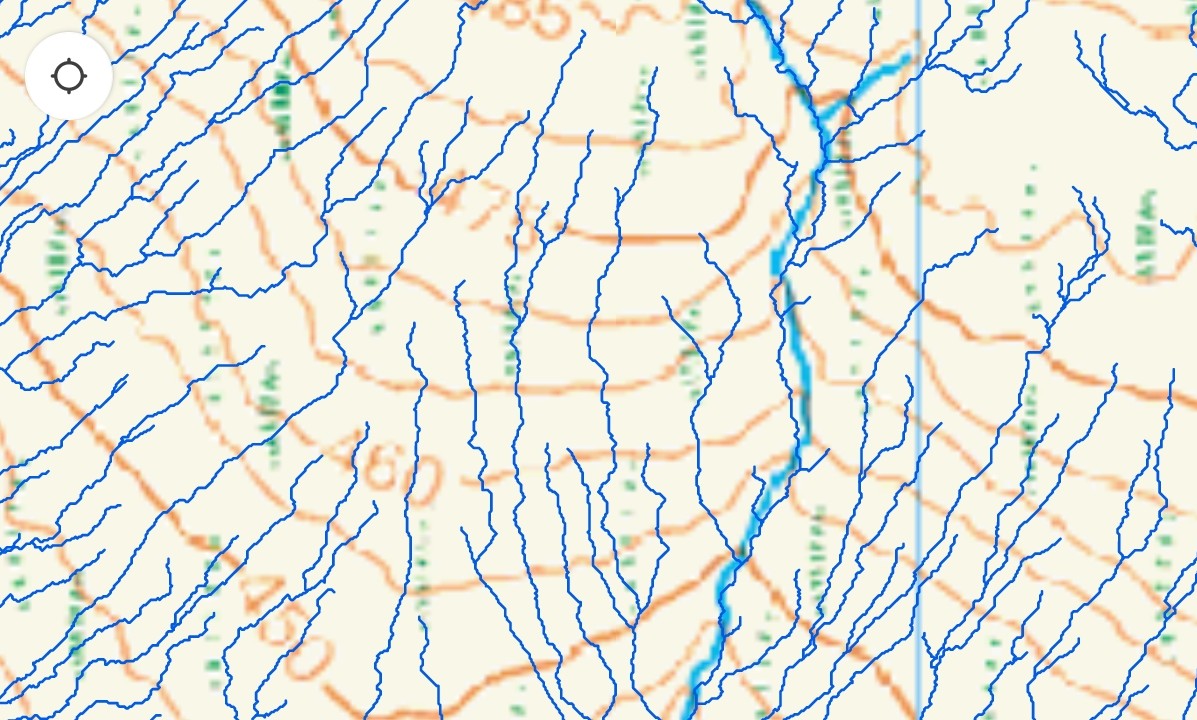

A screenshot of the tablet. Each blue line represents a possible gully.

My tablet displays a map overlaid with what looks like a tight network of blue veins. This map has been produced using LIDAR data – an airborne mapping technique which accurately measures the height of the terrain and surface objects on the ground. On this map, each blue line represents the location of what is probably a channel. If these channels are caused by erosion of the peat, we call them erosion gullies, and our aim is to halt this erosion by blocking them up. Between us, over the next few weeks, we will walk every single line. We’ll record each opportunity to construct a mini-dam, or gully block, along with measurements and recommended material – peat, stone or timber. From this, we’ll create a restoration plan and in the next couple of years a contractor will be here, enacting our instructions, creating mini-dams in the erosion gullies and planting sphagnum moss. It feels like a big responsibility!

A gully blocked with a stone mini-dam on Kinder Scout

I’ve been passionately writing and talking about peat, bogs, sphagnum moss and moorland creatures on a daily basis for over five years, in my role as a communications officer for Moors for the Future Partnership. I love the moors, visiting them often for runs and walks. But normally, I don’t actually do the practical work. Now, the conservation team have a tight deadline and I’ve jumped at the chance to help with the survey.

After two training days with the team, ensuring my skills are up to scratch, how will I fare on my first solo day, armed only with a tablet and bamboo cane, which is part walking-stick, part peat prodder?

A moorland pool reflects the winter sunshine

Up on the moor, we plan which sectors we’re each going to cover. We set off in different directions; I head off up the hill, right into the heart of the moor in eerie mist. Suddenly I’m alone in the middle of nowhere. I hear red grouse taking off with their characteristic “go back, go back, go back” call, and ravens caw overhead. So it begins – following a blue line on the tablet to its end, deciding if I would insert any mini-dams into the channels, thinking about how water flows, moving slowly over tough terrain.

Alien-looking lichens and mosses

I am awestruck by how much this moor changes as I walk around it. Normally, when I walk on the moors, I’m on a path, and moving relatively fast through the landscape. Today, I’m exploring every inch of the moor, and it’s striking just how much variation there is. One moment there is spongy sphagnum moss, the next moment springy heather. Some patches have been mowed, and it’s a huge relief to walk on shorter vegetation as it’s much easier.

Sphagnum moss is abundant in this area

When people think of the moors, they probably think of the purple heather that is such an iconic sight, but if you take the time to stop and look, there is so much variety and colour. Dwarf shrubs like bilberry, tiny creeping bog cranberry, sphagnum mosses in a rainbow of hues, cottongrasses, star mosses and alien lichens.

Tiny bog cranberry plants thread through the sphagnum moss

The best bits are finding huge hummocks of sphagnum moss. There is sphagnum everywhere, with its fantastically varying colours and the implied understanding that where there’s sphagnum, the moor is in great condition. The sphagnum indicates that the peat is wet, and is a key indicator species that the habitat is healthy. Not much work is needed here, there aren’t many signs of erosion or drainage. Here in the Peak District, it is unusual to come across areas that have this much sphagnum, so it’s a joy to see.

Sphagnum moss comes in a fantastic array of hues

The mist clears, the sun comes out and it gets warmer. There is an immense feeling of peace and space here. Something about being all alone in this landscape is comforting. High up but cradled by gentle slopes and warm and alone, I can hear the plaintive cries of golden plover wheeling past in the distance.

I can hear golden plovers in the distance

I finish the section and converge with my colleague to eat lunch, check progress and compare notes. She’s been looking at a similar area on the other side of the valley. Neither of us have found many channels that need blocking, and we’re pleased to note that the upper part of this moor relatively healthy. We decide which areas we’re each going to cover next and set off down the hill.

More sphagnum moss, this time in orange

After lunch, everything changes. This area is covered by thick, deep heather, and the ground is much drier. There are lots of erosion gullies and holes in the peat, some of them very narrow but quite deep. This indicates that the integrity of the peat is damaged and it is dried out, leaving it susceptible to erosion. In some of the gullies, I can feel with my cane that the peat has eroded away completely, to the gritty rock layer. My job is to decide what work needs to be done, and to mark the size and type of intervention, and its location, on my tablet.

A recently created stone gully-block in a narrow channel, like the ones described here

Each gully will need to be blocked, every few metres along its length. I’m taking measurements and prescribing interventions, filling my tablet with information about work to be done – what kind of material, how deep, how wide, how close, where? I’m using my bamboo cane to measure the depth of the gullies, and of the peat, to help inform my decisions.

I casually drop the cane into a small gap in the heather where there is a narrow gully, expecting it to slide down a few centimetres and come to rest in the peat below. Instead, it disappears and I hear it hit water. Startled, I take a closer look. The hole is tiny, just a few centimetres across, but there must be a chasm below me.

Suddenly aware that the ground is less solid than it seems, I lie down to spread out my weight and reach as far as I can into the hole to try and retrieve my cane. I can’t reach the stick – it must have fallen at least a metre below me. I can feel that there is a big void below. I’m laughing at my rookie error but also quite shocked that what looks like solid ground is in fact undermined and unstable.

Looking into a peat pipe, heading upstream

This is probably a peat pipe – an underground erosion channel transporting water from the moor. Peat pipes are little understood and difficult to remedy, because unlike a normal erosion gully they are invisible, and you can’t tell where they start. My colleagues in our science team are researching them and looking into the best ways to intervene. What we do know is that they are often a cause and symptom of dry peat – and that dry peat is never good news.

A wide deep gully. Just a bit further upstream, this is a peat pipe - water runs out of it, but its top is closed. A large amount of gritty sand has washed out of it and been deposited here. This sand comes from the mineral layer below the peat, indicating that this erosion has cut all the way through the peat.

I carry on with the survey. Further down the moor, peat pipes have collapsed to reveal big gullies. It’s clear that water has been flowing swiftly out of the pipe here – piles of grit have been washed down the pipes and dumped here.

I feel disempowered without my cane. I hadn’t realised how much I was using it to keep my balance and understand my surroundings. I borrow a spare cane from my colleague and continue down the gully system. The further down the moor I go, the more mini-dams are needed. This area will need a lot of work and it’s satisfying to know that I’ve contributed to a plan which will help to restore this moor. Making so many decisions, and walking so far over tough terrain, has left me exhausted, and soon it’s time to head home. Walking off the moor, the moon has come out and the January sun is about to set. I feel as though I’ve discovered a whole new world in one day.

Find out more about Our Purpose

To support our work you can donate to the British Mountaineering Council's Climate Project.

The sun is setting is we head off the moor