New research has shown how a tiny moorland plant, sphagnum or “bog moss” can dramatically reduce the likelihood and severity of flooding downstream for communities at risk.

Six years ago, sphagnum moss was planted on Kinder Scout, the highest peak in the Peak District National Park, in an area which now forms part of the newly-extended National Nature Reserve (NNR), looked after by the National Trust. After planting, the impact of the moss was closely monitored and has now been proven to significantly slow down water running off the hills after rainfall, reducing peak streamflow (the maximum amount of water in a river after a storm), by 65%. There is a similarly remarkable increase in the time it takes the water to enter the river system. This has important benefits for communities downstream that are vulnerable to flooding, as it means that water is being released more slowly.

The findings of the six-year study, implemented by Moors for the Future Partnership, confirm the vital part sphagnum moss could play in a widespread and effective reduction in flood risk for vulnerable communities downstream. Planting sphagnum reduces both the likelihood and severity of flooding. Natural Flood Management (NFM) uses natural processes to reduce the risk of floods and droughts, making catchment areas more resilient to the impacts of climate change and extreme storm events.

Sphagnum moss is key to the ecology of our invaluable wetland areas of upland blanket bog. As well as performing the crucial role of accumulating over time to create new layers of peat – an essential carbon store – sphagnum is able to absorb up to 20 times its own weight in water. A healthy sphagnum covering will protect and maintain the wetness of the peat underneath and, as these findings have shown, hold peak water flow on the hills, rather than allow it to overwhelm river systems below.

Moors for the Future Partnership undertook extensive planting of sphagnum for the study as part of its flagship, EU LIFE-funded MoorLIFE 2020 project. Over 50,000 sphagnum plugs (sphagnum plants approximately the size of a 50 pence piece) were planted by hand in areas of the Kinder Scout NNR previously restored from bare peat by the Partnership.

The site has formed part of an ‘’Outdoor Laboratory’’, created in 2010 to study the impacts of restoring peat compared to leaving it bare. This comparison is providing valuable data to help improve understanding of the benefits of a healthy peatland, including its important role in Natural Flood Management. This pioneering scientific monitoring site was instrumental in Natural England’s historic decision to increase the size of the Kinder Scout NNR by 226 hectares in August this year.

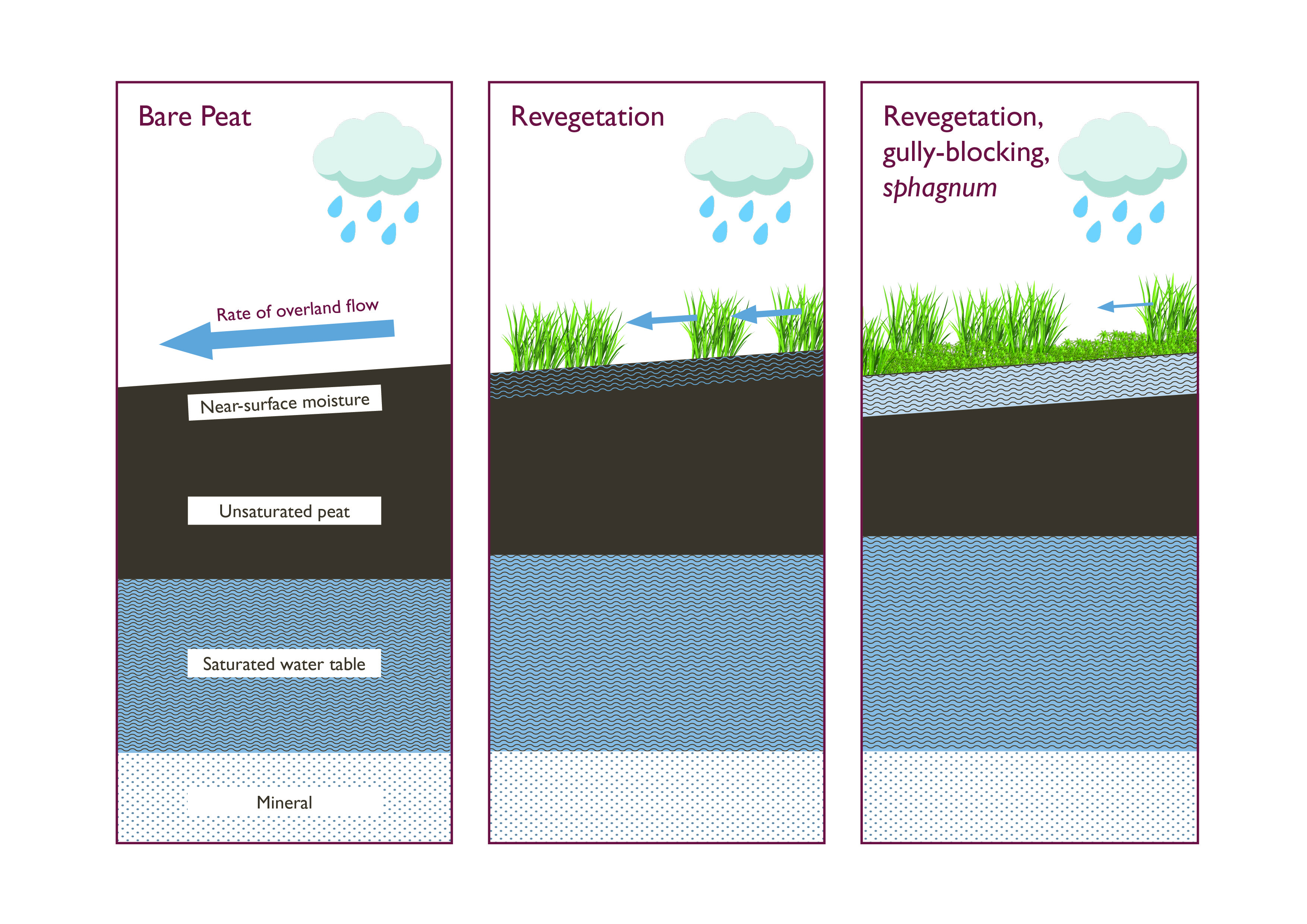

Just over 10 years ago, the area on Kinder that is now carpeted in bog moss was a large, barren area of bare peat. With no vegetation to hold water or stabilise the peat beneath, any heavy rain will wash straight off the hills into streams, carrying valuable peat with it, flowing quickly down into the valleys. In storm events, this will lead to large surges of water entering the river system, which can then result in severe flooding for communities further downstream.

The reintroduction of sphagnum has significant benefits for the catchment. As the sphagnum grows and thickens, it creates a dense, rough surface over the peat, which slows down the water as it flows across the catchment and into the streams. Storm water is fed into the river system more gradually, which reduces flood risk or severity down in the valleys. The new study reveals that, over the years, these benefits are continuing to improve because the sphagnum is continuing to grow. The sphagnum trial site on Kinder Scout is a relatively small area, but extensive sphagnum planting has also occurred across the Peak District, South Pennines and West Pennines. When applied on a landscape scale, the impact of the seemingly small – but mighty – bog moss, would be global in terms of climate change, water quality and flood severity.

This most recent study consolidates modelling from Protect NFM, an ongoing NERC-funded project, which has demonstrated that upland restoration offers a low-cost way to reduce the risk of flooding in vulnerable rural communities and to optimise multi-benefit restoration work for NFM. Protect NFM has found that if the restoration at the “Outdoor Laboratory” on Kinder (including the dense sphagnum planting) was replicated across the landscape, peak storm flow could be reduced by up to 12% for communities in the shadow of Kinder Scout, including Glossop, a town in Derbyshire’s High Peak where risk of flooding is high. In short, intense storms, peak storm flow could be reduced by up to 24%.

As part of the MoorLIFE 2020 project, Moors for the Future Partnership also looked into the effects of introducing sphagnum on peatlands where other native moorland plant species are dominant, namely heather, cotton grass and purple moor-grass. Three years into the study, monitoring has already shown that sphagnum planting into dense heather may have slowed the flow of water from the hills. It is likely that this effect will increase in future years as the sphagnum continues to grow and spread.

Research and Monitoring Officer at Moors for the Future Partnership, Tom Spencer, says,

The risk of flooding is increasing all the time as our climate changes and we see more frequent extreme storm events. Effective NFM strategies have never been more important, and these remarkable findings prove sphagnum planting on peat moorland to be a powerful tool in minimising the risk and severity of flooding.

A 65% reduction in peak streamflow and a huge 680% increase in lag time between rainfall and that rainwater entering the river system are startling results, with far-reaching benefits for communities downstream.Our study shows the effects of successful sphagnum reintroduction in just one area and the effects on the catchment are dramatic. Imagine these impacts on a landscape scale.

These findings reinforce research from other NFM projects, such as Protect NFM and Making Space for Water, to produce a strong body of evidence supporting extensive sphagnum planting as an effective, low-cost tool for flood management. As our changing climate sees increased flood events and severity, this ‘superhero’ moss could make a real difference.

Chief Executive of the South Pennines Park, Helen Noble, says,

These sphagnum planting findings are fantastic news for the communities that are most vulnerable to flooding in the South Pennines.

As our climate changes, the risk and impact of flooding is increasing. Flooding events in 2015 and 2020 caused devastation to villages and towns in the South Pennines Park, causing extensive damage to homes and businesses and with floodwaters rising so quickly that people had to be rescued from their cars.

It has never been more important to build natural flood resilience into our landscapes, both for the natural environment and for communities at risk. These results from Moors for the Future Partnership’s research show that extensive sphagnum planting could play a huge part in preventing future flood devastation.

The research behind this article -

Ecosystem service impacts of degraded blanket bog restoration, Summary (1 of 7 Chapters)

Ecosystem service impacts of degraded blanket bog restoration Introduction (2 of 7 Chapters)

Ecosystem service impacts of degraded blanket bog restoration, Stream Discharge (5 of 7 Chapters)